69 results found with an empty search

- Craig Larman on 10X and The Future of Jobs

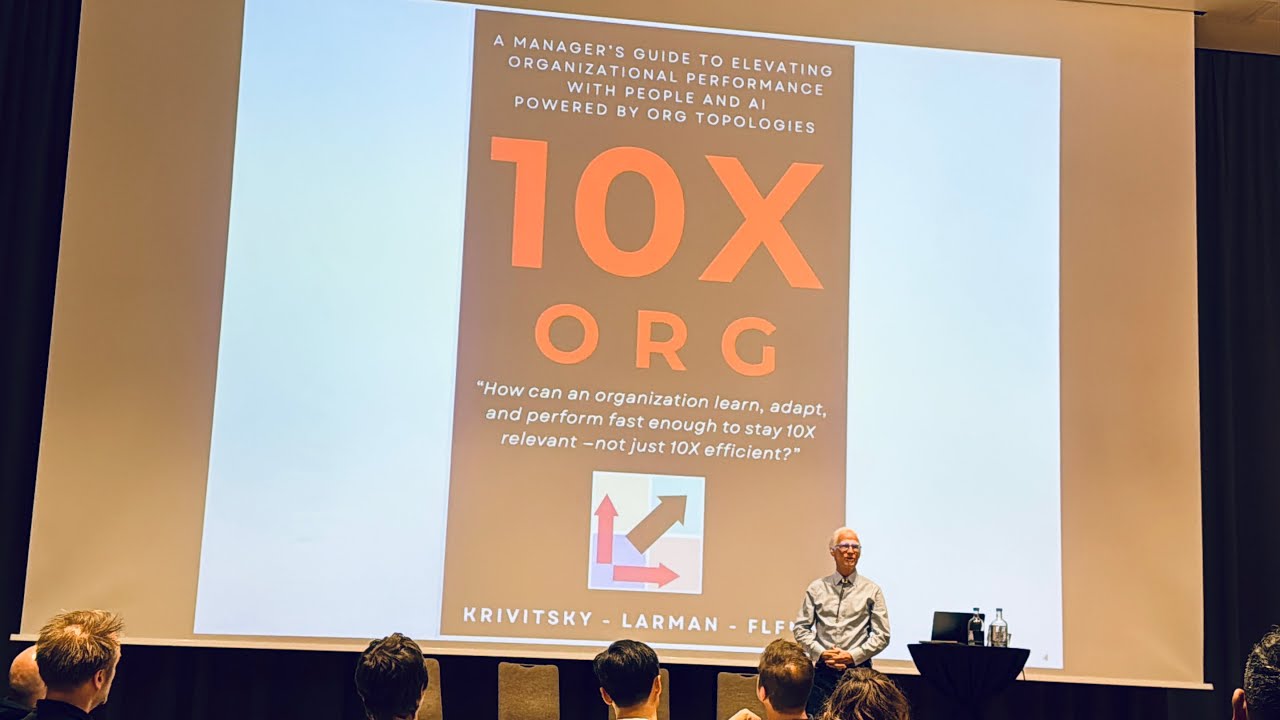

I am here to save jobs for our children. Here is the video of Craig Larman speaking at LeSS Conference 2025 with a full transcript below. "This is my new professional mission for perhaps the next 10 or 20 years. And you can, those of you who have been at the previous conferences with me understand my motivation for this and our grandchildren. I have grandchildren. So my thesis is I've shared each year in these keynotes since 2020. That within a few years, maybe by the, maybe by October, 2027, we'll see news of the first job category that's been meaningfully replaced by an AI. I think that could be possible within two years. I've got a sister and a daughter who work in the film industry and you should see what's happening there. Things that currently take 1000 - 2000 people to do a production it's just, dramatically dropping and on. Of course, these are very early days, so I understand that it sounds like I am crying wolf or describing a situation that isn't going to happen. But I think this could be a boiling frog dynamic over the next 10 years. And of course, these things are gonna be cheap as dirt. They work 24/7. They don't ask for vacation. They don't ask for time off. So the labor economics incentives to replace humans by AIs will be compelling, I suggest. And we humans won't compete. If the only thing that we can suggest is, please hire me, I'll make you 10% better. It's just not gonna cut it. I suggest, because these AIs are going to be so economically desirable. Cheap as dirt, good enough, no vacations, that if humans want to be attractive in the future labor market, I suggest that 10% isn't gonna do it anymore. Now, if you've read the Book of "Secrets of Consulting" by Gerry Weinberg, what do you know? One of Jerry's chapters is "never recommend more than a 10% improvement in business". And there's a whole bunch of interesting reasons for that. And I suggest that at this, what's going to be coming milestone or disruption in intelligence-as-a-service that we're going to have to suggest something more ambitious. And I call this "10X Org". So the idea is, as in LeSS, one of the guides is more outcomes, less outputs, the focus is on some business impact or some meaningful impact, not just on creating outputs. And so when we say "10X Org", what I'm trying to suggest is 10 times the amount of business impact, 10 times the market share, 10 times the revenue. Or whatever the business impact is. And I think that although before the age of AI, it would've been ludicrous to have these kinds of messages or suggestions, as a consultant. I think we're gonna be entering an age where aspirationally we need to make that pitch. And aspirationally, we humans will have to step up our game if we want to compete to actually achieve this goal. And so I think we're at a point in the industry where actually we can be bold and suggest a much deeper improvement than would've seen ludicrous before. And so with Roland and Alexey. Roland and Alexey! Over the last year, I've been starting to explore how to do this and the three of us are working on a book together, which we're gonna be releasing in not too long. And the basic idea, if you think of this from an Org Topologies point of view, this is Org Topologies as a 2x2, and quite simply where the scope of skills mandate is high and the scope of work mandate is high, that's the quadrant that is adaptive. And this has always of course been the message of LeSS. But what we're trying to do with Roland and Alexey with the "10X Org" message is expand this to a far broader audience to all the different markets that are gonna be affected by AI. And I suggest that in many of these, moving to this quadrant is the fighting chance for our children to have good jobs. The adaptive quadrant. And it's also, I would suggest the perfection vision of where LeSS gets to as well. Thank you."

- Case Study: Using Org Topologies™ to Analyze the Agile Transformation Journey at a Large Dutch Bank

TL;DR This article analyses the transformation of a major bank with org topologies. To understand this article, you first need to know about Org Topologies ™ . Summary of the transformation analysis: An organizational design can be implemented iteratively and incrementally. There is no need for "first time right". There is a need for an opportunity to learn the new design by experiencing it. Org topologies help implement organizational change in a structured and controlled manner. A shared transformation goal is necessary to achieve good results. Org Topologies helps to define a visionary overarching perfection goal, enabling everyone to understand the underlying principles. Employees need to be able to make autonomous decisions that will contribute to achieving the perfection goal. Org Topologies is an enabler that places the mandate for continuous improvement of organizational design in the hands of employees, at the lowest levels of the organization. If the org design perfection goal is too ambitious, it will jeopardize the transformation. "Too ambitious" happens when people reject the goal. Therefore, combine an unambiguous perfection goal with transformation sub-goals and use them as "Stepping stones" towards perfection. Mapping and naming intermediate sub-goals creates a clear picture of the maturity level, relative to the overarching perfection goal. This enables parts of the organization to focus on improvements that are most important for their specific context and provides an objective way to track progress . The success of each step in a transformation journey depends in large part on the extent to which employees (team members and management) can take ownership of the change. The unambiguous vocabulary and transparency provided by Org Topologies help achieve this. The transformation This transformation was rolled out bank-wide: About 3,000 people faced a change of work, a change of team, and/or a change of way of working in early 2022. Preparations for this took about a year and a half. The entire organization "flipped" to the new model in one go in March 2022. My role in this transformation was to "nudge" the organizational design with LeSS principles. The target model became a home-brewed mix of Team Topologies and LeSS. The main changes were: unified governance, continuous improvement, mandate low in the organization, and separation of the WHAT and the HOW. For the latter, the organization was split into a part for producing products and services (the WHAT) and for provisioning knowledge for it (HOW). In this paper, I focus only on the product development organization (the WHAT). Iterating on an initial design I observe in larger organizations that quite some time is spent on designing the future organizational blueprint. That's because changing the organizational structure is complex and risky. When the design phase is over, it is implemented with a big bang. The big bang approach creates clarity and reduces costs because no temporary structures need to be rigged to support a hybrid situation. A disadvantage is that it can create chaos because everything is suddenly different. Agile people like the clarity of the big bang. But we don't like a separate design phase. These two concepts can be combined by creating an initial organizational blueprint and releasing it on a flip date. We assume the initial blueprint is good enough, but not perfect and probably incomplete. After the initial release, we start iterating by applying smaller changes incrementally. This allows us to grow toward perfection guided by feedback loops. For such an approach to work, everyone needs to clearly understand that the implemented model is a starting point or a step of a journey. Also, everyone needs to be able to assess what are good and not-so-good adjustments to the model. Org Topologies™ is invaluable here because it visualizes the current position, the first step, and the perfection goal, allowing the continuous change to be kept "on track" by the employees themselves. Transformation goal: Uniformity The overarching perfection goal of the new organization was PART-3. In addition to that perfection goal, first steps towards that greater goal were proposed in the initial design. That first step was implemented bank-wide in early March and had a different design for each value area (called "Hub"). The design of the 15 new value areas on the flip date was not one single archetype but a mix of archetypes depending on the context within the value area. This meant that in all Hubs, the TASKS-1/TASKS-2 archetype was dissolved and replaced by: CAPS-2 archetypes (teams with their own Backlog and PO). One or more PART-2 types (1 PO, 1 PBL with two to six teams). Some PART-3 (fully end-to-end) value area. Achieving the more perfect archetypes has more and different challenges and implementation involves a higher degree of uncertainty. Somehow it made sense to migrate in a controlled way instead of creating the utmost chaos everywhere in the company. Despite each value area (Hub) having its own implementation of various archetypes, there is uniformity. In a transformation of this size, there is no "one size fits all" precisely because the starting positions are heterogeneous. Uniformity should not be sought in "everything is set up the same", but rather by: the unambiguous basic principles of the model, the formalized communication structures, the shared understanding and transparency about the journey. I believe we would have succeeded in this better and more easily if we'd had Org Topologies at our disposal. Language is important for ownership of the future model I visited many business units in the preparatory phase towards the flip date. One thing that struck me was that knowledge about the envisaged model and its underlying principles was insufficiently known by employees. And without understanding, no acceptance and hence no ownership of the new model is possible. The model did contain a new, common vocabulary, but we did not succeed very well in sharing it across the organization. Somewhere, something went wrong in the communication from the Transformation Office to the shop floor. The reason: Indirect communication from the heart of the transformation passed on via insufficiently informed management layers to the employees. This resulted in a range of differences in the interpretation of the content and operation of the new organizational model. Having a common vocabulary is an aspect that is offered by Org Topologies. Moreover, that vocabulary is not company-specific, which allows comparison between companies. Reporting on progress Progress reporting is always asked for and this bank was no exception. The transformation had been cut into phases and metrics were needed especially for the roll-out phase. Unfortunately, spreadsheets with tick lists were used. The agile coaches were instructed to get the lists ticked off on time. You will see this did not lead to understanding and ownership of the transformation but generated a lot of resistance. Moreover, it did not provide a transparent picture of our actual state. The Org topologies model offers a powerful and transparent solution. The model helps to describe the current situation and the change ambition per value area in archetypes to be implemented. The result is measurable by the decrease in the number of teams per PO/PBL (vertical axis) and the decrease in technical dependencies (horizontal axis). Some examples The overarching perfection goal for the future organization was PART-3. But planning and execution turned out to be two completely different things. I will use some examples to explain the movements of the organization at the bank. I will use the Org Topologies archetypes to show that things were less messy than they might seem at first glance. The bank was extremely heterogeneous before the transformation. It was a classic top-down driven organization, split into Business and IT. On the Business side, I mainly saw the TASKS-1 archetype: departments surrounded by a matrix structure for projects and initiatives and programs led by steering committees. A single department was of the CAPS-2 type (feature-focused interdependent teams, reasonably functioning SAFe). This was the bank's flagship department. In IT, it was mainly TASKS-2 archetypes: Component teams with task-level backlogs (poorly functioning SAFe). Example 1: The situation at HR, archetype TASKS-1 HR was not working agile yet, just like the vast majority of the organization. Although the department leads themselves thought otherwise. They translated being Agile into "working demand-driven". HR was of the TASKS-1 archetype. The department managers distributed the work in their Management Team meetings, called "MTs". I found that they often were in those MT meetings. The meetings lasted long, often a whole day. The managers discussed the various projects and priorities and split the work into tasks. These tasks were then assigned to the "usual suspects", which are the people who already have knowledge and experience of the required topic or technology. They also included available capacity in the allocation without involving the employees themselves. Then ad-hoc teams were set up to do the work. Those teams were tasked with carrying out the work and reporting on progress. Employees were usually in several teams at the same time and had to do "regular work" too. This way of managing product development is characterized by external coordination, external decomposition of the work, hand-offs, and extreme specialization. It leads to high workloads for both management and employees. The HR director asked me to help make their work process "more agile". My idea was to try to bring this TASKS-1 to a PART-3, i.e. 1 backlog for HR with the HR director as PO. However, the HR managers were not ready for this. They proposed CAPS-2: a separate backlog for each manager with responsibility for a particular journey (employee life cycle, recruitment, healthy and fit, ...). To get used to working in Sprints with fixed teams, I thought this was a good enough starting point. I foresaw that due to the dependencies between the journeys and the micro-management of the managers, this setup would lead to new problems for which the next step to PART-3 could become a realistic option. There was a danger in maintaining the existing management structure alongside the introduction of component-team Scrum. I foresaw that this would lead to dumping the Scrum experiment again. My approach was to dismantle the existing pattern in service of the org change. After all, the long MT meetings were a bottleneck that needed to be resolved. We started the movement towards CAPS-2 by removing activities from the MT meeting. We delegated them to the Scrum teams, except the Sprint Review. A joint Sprint Review was a logical start to grow towards PART-3, where the Sprint Review is a central event for the entire value area. Example 2: In the IT teams, TASKS-2 archetypes The IT department consisted of specialized component teams. There is a huge variety of tools, applications, products, and systems in use. And they had not yet succeeded in simplifying the architecture and infrastructure. The core banking systems, for example, are old and very specific. It makes no sense and the risk is high for all teams to learn these systems. For these environments, the choice was made to stay in TASKS-2. In Team topology terminology, these would be called "Complicated subsystem teams". Other IT teams with more common technology (such as Pega), were merged with business specialists into cross-functional teams. These were mostly CAPS-2 archetype teams. They could not deliver a full end-to-end product. In the preparatory phase, significant architectural changes were implemented to reduce dependencies between value areas and CI/CD, and provisioning (AWS) low-code/no-code solutions were devised to move the teams closer to the rightward columns of the Org Topologies map. Here and there, a single CAPS-3 or PART-3 area could be formed. Example 3: Mortgages and business banking, from TASKS-2 to CAPS-2 and PART-2/PART-3 The bank's flagship branch was Mortgages. They delivered faster and were better organized compared to the rest of the bank. This was because, as a forerunner, they had moved away from the standard TASKS-1 archetype. They had moved to the TASKS-2 archetype with the introduction of SAFe. The dynamics that prevailed here will seem familiar to you: Days of planning events focused on coordinating dependencies, low predictability of delivering customer value, lots of handoffs, frustration, and sense of powerlessness among the teams, and lack of learning by the group as a whole. This area did have a few exceptional teams doing "reasonable" SAFe. These CAPS-2 teams delivered specific front-ends with minimal dependencies on the back-end systems. The Mortgages value area implemented the SAFe framework because it provides clear guidance for scaling cross-team coordination. I remember the conversation I had with the Director of Mortgages about this. After seeing the PART-3 archetype (one consolidated backlog per area, end-to-end cross-functional teams) and the routes leading there, he realized that institutionalizing coordination is precisely the limitation of the SAFe model. He saw that SAFe does not focus on solving the root causes of the coordination need. Instead, SAFe keeps specialized component teams (horizontal axis of the Org Topologies map) with narrow domain knowledge (vertical axis) intact. His insight was reinforced by his experience with their very best teams; after all, they were already at CAPS-2 level in that they fully knew their domain and had virtually no technical dependencies with the rest of the organization. Some consultants might argue that the above result is not a successful transformation because of the presence of TASKS and CAPS-archetypes. I agree that migrating to an CAPS-type is in general not a good option because it offers too few advantages over the TASKS-types. I share the view that migrating to a PART-type archetype is better because the key de-scaling concept of multiple teams with one backlog adds substantial value. Some say CAPS-types should be avoided because the concept of a single backlog per team is difficult to roll back once implemented. I think we should not be afraid to allow CAPS-types in larger organizations if they are a step toward perfection. I consider CAPS-types bad when they are an end-state. In larger organizations we need to make a trade-off decision: Do we force PART-level as the minimum (consulting) or do we allow less adaptive archetypes and let the customer find their own meandering path (coaching)? In large transformations (hundreds of employees), I see the benefits of CAPS-types being set up alongside PART-archetypes as an intermediate step toward perfection. In smaller organizations (up to 50 people), CAPS-types are not a sensible option, implementing PART-2 is not the biggest success and a WHOLE-4 is the best achievable result. Using Org Topologies, we focus on a journey with a clear perfection goal and we have a good tool in hand to monitor and drive change towards an unambiguous perfection goal. Conclusions Org topologies™ provides support in a number of areas that can improve the journey of continuous organizational design adaptation: Structure of and control over the change process Meaningful progress monitoring (can be used as a maturity model) Transparency about the shared transformation goal Ownership of the transformation by the employees Controlled context-dependent variations of the organizational design Improved communication through unambiguous language (C) 2022, Alexey Krivitsky and Roland Flemm. Org Topologies. This experience report presents a personal view on the change story by the credited writer. Should you have alternative views or additional details about this particular company's change story, please do not hesitate to contact Org Topologies and submit your version for publishing.

- AI Won’t Fix Silos — Org Design Will

Everyone is racing to adopt AI. Developers are coding faster with Copilot. Analysts are producing reports with GPT. Recruiters automate job descriptions, and marketers launch campaigns in minutes. But most of these initiatives only create local productivity boosts . Teams move faster in their own silos, while the big initiatives — the bold moves that actually matter to customers and strategy — remain stuck. Why? Because the wrong organizational design doesn’t just slow you down; it actively blocks progress . Layer AI on top of dysfunction, and the dysfunction only accelerates. Resource Topology: Faster Silos, Slower Outcomes In a Resource Topology , work is divided into specialized units (people, departments, teams). Analysts hand over specs, developers code, testers check, and an integration team stitches it all together at the end. This design optimizes for utilization, predictability, and centralized control. Add AI into the mix, and each unit becomes faster. Alaysts can deliver specs faster, leads can do more efficient planning and work prioritization. Developers produce more Android code per day, and testers can automate scripts in seconds. There is definitely progress. But when we look closer, we see that the overall speed of the system doesn’t improve . That is because adding AI does not change the way the system works. We still have handoffs between units, and they multiply the delays in the work. Decision-making remains unclear, creating noise in the system as work is bounced between units with limited mandates. Distributed decision rights, tied to risk and audit processes, restrict automation instead of enabling it. The performance gain is local, resulting in Faster queues, with slower outcomes . A classic law of systems thinking comes into play: “The performance of a system depends on how the parts fit together, not on how they perform taken separately. When you optimize the parts, you sub-optimize the whole.” (Russell Ackoff) The logical path of evolution is obvious. The narrow, repetitive roles in these silos are replaced by AI agents. That optimizes local productivity gains and cost savings. But it doesn’t make the organization as a whole more adaptable. In fact, it leaves the system as rigid as before, creating queues of work between AI agents. The plus (+) symbolizes an AI-equipped unit In a Resource Topology, AI typically delivers local wins. Assistants are deployed inside existing silos, which makes individual units faster but has little effect on end-to-end outcomes. The handoffs, approvals, and fragmented data flows remain unchanged, so queues continue to grow. Because decision rights are distributed across many groups, automation is limited and often slowed down further by risk and audit processes. The focus remains on optimizing local output, rather than improving the system's overall performance. Delivery Topology: Faster Streams, but Still Rigid Many organizations have evolved into Delivery Topologies. Cross-functional teams are restructured into value streams. Instead of analysts and developers working separately, they sit together and ship features from start to finish. In the best scenario, they have all the skills in the team needed to deliver end-to-end items of work. This is a genuine improvement. When we add AI to these teams, it will accelerate each value stream — features get delivered more quickly, backlogs shrink, and the teams feel empowered. The mortgage team, for instance, can now process applications end-to-end with remarkable speed. But there’s a hidden ceiling. Each stream is still a silo, locked into its own domain. The mortgages team won’t deliver insurance. The insurance team won’t deliver business loans. When a new customer need arises, the organization must spin up a new silo to serve that need. This design optimizes for speed at the team level and delivers what is already known . This system is fast at the value stream level, but not highly adaptive. Every strategic pivot requires reorganization. And although the value streams are fast, in the long run, they will stop producing value. That is due to the law of diminishing returns : once AI has extracted most of the speed gains from each stream, the cost of changes begins to outweigh the value, even when change is cheap. There is no more value for the customer in yet another change to the mortgage processing. Leaders will apply cost-saving measures — replacing people with AIs in routine parts of the value stream. Again, it creates local efficiency, but not systemic adaptability. In a Delivery Topology, AI produces mostly local improvements. AI assistants are deployed inside individual silos, which speeds up work but has only a limited effect at the value stream level. Innovation ultimately caps out because it is confined within these narrow value streams. The emphasis remains on optimizing local outputs, not on unlocking broader organizational performance. Adaptive Topology: Where 10X Becomes Possible True transformation comes with the Adaptive Topology . This design is not very common. It requires giving teams of teams the mandate to work on the whole business problem or customer need , not just a slice of it. And equipping them with all the skills and tools required to succeed. In an Adaptive Topology, people are multi-learners. They acquire knowledge across domains, enabling the team of teams to deliver outcomes autonomously. They refine work together, resolve dependencies directly, and coordinate face-to-face rather than through endless external handoffs. Here, AI shows its full potential. It is not trapped inside silos. It is applied to shared outcomes. Models are trained on customer data to spot shifts in demand. Generative AI accelerates prototyping and validation across the whole problem space. Moreover, cross-cutting concerns such as legal, security, and compliance are embedded, so everything produced complies to the standard requirements by design. In this environment, there is no need for disruptive reorganizations when strategy changes. Adaptation is built in. People and AIs collaborate holistically to learn, innovate, and deliver. And because people are multi-specialists — “M-shaped” instead of narrow — they are not candidates for replacement. They are indispensable. AI doesn’t reduce their relevance; it amplifies it. In an Adaptive Topology, AI is applied to shared business outcomes, which amplifies collective learning and impact. Because AI is integrated holistically, there is no overhead from fragmented, decentralized implementations. The system is holistic from the start, and AI strengthens that quality. First Design, then AI. The archetypes in each quadrant of the map will have specific benefits of an AI Adoption: Every organization has a design. Yet most leaders underestimate how profoundly the org design shapes the impact of AI. Without redesign, applying AI guarantees disappointment, because the expected gains are unrealistic. The contrast is clear: Resource Topology → AI delivers local efficiency, but the system remains stuck. Delivery Topology → AI makes teams faster, but the organization stays rigid. Adaptive Topology → AI amplifies adaptability, enabling the whole business to move in sync with strategy. AI does not fix design flaws. It amplifies them. To unlock its promise, leaders must first design organizations fit for change — and only then bring in AI. More on this AI and value streams in this video recording . More on Strategic AI . More on elevating to the Adaptive Topology .

- Creating 10x Orgs: Breaking Free from Value-Streams

Meet Alexey, creator of Org Topologies, to learn about rethinking the structures that almost likely keep your product development frozen in time, limiting the org's true potential. Most orgs get locked into rigid value-stream models—great for predictability but brittle in the face of change. This session shows how to 10X your organization’s adaptability and innovation by shifting from narrow value-streams to multi-learning, decentralized teams, and AI-enabled continuous learning. An online meetup recording: 13 Aug 2025

- Reactive to Creative Leadership in Org Topologies

TL;DR In modern organizations, leadership style and organizational design are deeply interconnected. When we talk about Org Topologies (Resource, Delivery, Adaptive), we usually think of structure. However, structure doesn’t shift without leadership shifting as well. The Leadership Circle gives us a useful lens here: Reactive leadership is fear-driven. It leans on control, compliance, and protecting one’s image. It stabilizes, but it stifles learning. Creative leadership is purpose-driven. It emphasizes vision, trust, collaboration, and systemic improvement. It unlocks adaptability and innovation. Org Topologies show us the organizational side: Resource Topology is siloed and efficiency-focused. Delivery Topology is cross-functional and output-focused. Adaptive Topology is versatile, outcome- and learning-focused. Now put them together: Resource Topology runs on Reactive leadership – command, compliance, and tight control. Delivery Topology needs a blend – Creative “achieving” combined with just enough Reactive discipline to keep flow predictable. Adaptive Topology thrives only under Creative leadership – visionary, empowering, learning-oriented. This article examines two frameworks – The Leadership Circle (which differentiates leadership styles, notably Creative vs Reactive orientations) and the Org Topologies model that describes different organizational design archetypes. We first summarize each framework’s core components, then map how various leadership styles align with each type of organizational topology. Finally, we discuss how leadership development needs to evolve as an organization shifts from one topology to another. The Leadership Circle Framework: Creative vs. Reactive Leadership The Leadership Circle framework (often delivered via a 360° Profile assessment) divides leadership behaviors into two primary categories: Creative Competencies and Reactive Tendencies . The Leadership Circle is a model that maps leadership behaviors and mindsets into two overarching orientations – Reactive and Creative – each of which represents a distinct way of leading organizations and people. Like Org Topologies, it offers a map of different archetypal patterns. Each half contains specific dimensions that capture a leader’s internal assumptions and outward behaviors: Creative leadership is characterized by effective, growth-oriented behaviors. Leaders high in Creative Competencies “achieve results, bring out the best in others, lead with vision, act with integrity and courage, and improve organizational systems” . For example, creative dimensions include Relating (building teams, developing others) and Achieving (setting vision and accomplishing strategic goals) . These competencies stem from inner confidence and a focus on purpose rather than fear. Notably, leaders who score high on the creative scale tend to be far more effective. High Creative leadership correlates strongly with better leadership performance and business outcomes. Reactive leadership is associated with self-limiting or fear-driven behaviors that can constrain effectiveness. The Reactive Tendencies reflect inner beliefs that limit a leader’s authentic expression and impact . Examples include Controlling (a tendency to micromanage, push for perfection, and derive self-worth from being in charge or “on top”) and Complying (a tendency to seek others’ approval and follow others’ expectations to feel secure). Such leaders often emphasize caution, control, or defending their image over innovation and engagement. In the Leadership Circle Profile, high reactive scores are inversely correlated with leadership effectiveness (often coinciding with low creative scores). In short, a predominantly reactive “command and control” style may undermine a leader’s impact, whereas a creative, empowering style enhances it. In summary: Reactive leadership optimizes for safety and control. Creative leadership optimizes for trust, learning, and purpose. The Org Topologies Framework: Organizational Design Archetypes Org Topologies is a framework for strategic organizational design that maps out archetypal ways to structure an organization. It introduces a visual mapping technique using two key dimensions of org design and defines multiple archetypal unit types. Sixteen base archetypes (team or department patterns) are categorized into four groups, and, importantly, these are distilled into three distinctive organizational “topologies” – common overarching patterns of how work and authority are organized . Each topology represents a fundamentally different organizational ecosystem with particular characteristics and fit-for-purpose use cases . The three topologies are summarized below: Resource Topology: A siloed, efficiency-oriented design with frozen functional roles and high specialization. Here, work is divided among specialized units (e.g., separate functional departments), and resources are managed to be 100% utilized. Leadership in this topology relies on top-down coordination – managers (or project management offices) plan work, allocate tasks, and monitor utilization across narrow skill silos. Because each group only performs a fragment of the process, extensive handoffs are needed for end-to-end delivery. Learning and innovation are limited; improvement tends to occur only within one’s specialization rather than through new discovery . Use case: Resource Topology fits stable environments where maximizing resource efficiency and specialization is the primary goal (e.g., a project-based organization hiring specialists for defined tasks). Delivery Topology: A fast-flow, output-focused design that upgrades to cross-functional teams delivering value with fewer dependencies. Compared to Resource Topology, work in Delivery Topology is organized into independent delivery units (e.g., feature teams) that can produce “completely done” increments with minimal handoffs. This is often likened to a “feature factory” – teams churning out a steady stream of features for a product. There is a strong focus on outputs and local efficiency (throughput of features), and teams are kept narrow in scope so they can deliver quickly and predictably. High-level analysis or product decisions are still handled by “directing” roles or upstream units (product managers, analysts), meaning discovery of what to build remains somewhat separate from delivery . This topology excels when the challenge is not figuring out what to build (the requirements are known and of proven value) but rather delivering it rapidly at scale. Use case: Delivery Topology is well-suited for environments where predictable, speedy delivery of features is critical and the market/problem is well-understood (for example, a software company rolling out frequent minor enhancements or a restaurant kitchen executing a set menu) . Adaptive Topology: A highly adaptive and innovative design that merges directing, doing, and delivering into unified, empowered teams. In Adaptive Topology, traditional functional boundaries are dissolved; instead of silos, the organization might form a “team-of-teams” or network of multi-skilled teams that work in unison across the entire value stream . The goal of this topology is to maximize adaptiveness – enabling easy, continuous change based on learning, and true customer-centric innovation . Teams (and individuals) in an adaptive org are expected to collectively discover what customers need and deliver solutions rapidly, adjusting course as necessary. This requires a culture of continuous learning, high autonomy, and synchronous collaboration (often supported by real-time data and AI tools to inform decisions). The design makes it “cheap and easy” to pivot strategy because teams are broadly skilled and tightly aligned with the overall purpose, not confined to narrow tasks. Use case: Adaptive Topology is fit for dynamic, uncertain environments where innovation and agility are paramount – for example, product R&D groups, startups, or market disruptors that must rapidly experiment, learn, and respond to change. It promotes long-term business resilience by enabling higher-impact outcomes and continuous adaptation. In summary , each topology serves a different strategic goal and entails a distinct organizational structure: Resource topology optimizes for resource utilization and specialization , Delivery topology for fast flow of outputs , and Adaptive topology for rapid learning and innovation (outcomes) . These differences in structure and goal create different demands on leadership style, as we explore next. Mapping Leadership Styles to Organizational Topologies The effectiveness of a leadership style is often context-dependent. A leadership approach that succeeds in a tightly controlled, efficiency-driven organization may falter in a fast-changing, innovative company, and vice versa. The Leadership Circle’s distinction between Reactive and Creative orientations provides a useful lens to map leadership styles onto the needs of each Org Topology. Broadly, as an organization’s design shifts from Resource → Delivery → Adaptive , the leadership culture must shift from predominantly Reactive (command-and-control, cautious, task-focused) to increasingly Creative (visionary, empowering, collaborative) to support the organization’s purpose. The table below summarizes this alignment: Organizational Topology Best-Suited Leadership Style (Leadership Circle) Organizational Needs & Rationale Resource Topology Goal: maximize efficiency & specialization Predominantly Reactive – directive, controlling style focused on stability and compliance. This topology’s siloed, plan-driven structure requires leaders who tightly coordinate and enforce standard processes . Reactive leadership tendencies (e.g., emphasizing control and risk-aversion) align with the need for predictability and utilization in a Resource topology, ensuring everyone follows the plan and stays “100% busy.” However, this can limit flexibility and innovation. Delivery Topology Goal: fast, predictable delivery of outputs Balanced/Transitional – leaning Creative (achievement-oriented) but with some Reactive discipline. Delivery topology introduces cross-functional teams and faster flow , so leaders must empower teams to own delivery while still maintaining focus on output targets . A Creative leadership approach that drives results and continuous improvement (high on the “Achieving” competency) suits this environment. Leaders foster collaboration and adaptiveness within teams, yet may retain Reactive elements like process control to ensure reliability and alignment with product requirements. Adaptive Topology Goal: continuous adaptation & innovation Predominantly Creative – visionary, empowering, and facilitative style. An adaptive organization needs leaders who inspire purpose, trust, and innovation . Creative leaders excel here by providing vision and strategy while empowering teams to experiment, learn, and self-organize towards outcomes. In this high-change ecosystem, reactive, control-oriented management would be counterproductive – as research notes, truly adaptive/agile cultures “require Creative Leadership” , and reactive leadership cannot easily usher in the needed innovation and engagement. Leaders must cultivate a culture of trust, agility, and learning, embodying competencies like Relating , Self-awareness , and Systems Thinking to enable the organization to thrive in uncertainty. As the table illustrates, leadership style and organizational topology need to be in sync . A mismatch can create friction – for example, a purely reactive, micro-managing leader will likely stifle an Adaptive topology that demands empowerment and quick learning, while a purely visionary, hands-off leader may struggle in a Resource-focused bureaucracy that expects tight control. In practice, organizations often evolve through these topologies, and leadership mindsets must evolve in tandem. Evolving Leadership Development as Topologies Shift Shifting an organization’s topology (e.g., moving from a Resource model to a more Adaptive model) is not just a structural change – it is a cultural and leadership transformation. Leaders must develop new skills and mindsets to support the new way of working. Below are some insights on how leadership development needs to evolve when an organization transitions from one topology to another: From Resource to Delivery Topology: Leaders need to shift from micro-management to empowerment as the organization moves toward cross-functional teams and faster delivery cycles. In a Resource topology, leaders were accustomed to detailed upfront planning, strict role boundaries, and ensuring compliance with plans. To succeed in a Delivery topology, they must unlearn the overreliance on rigid plans and resource control. This means developing more Creative behaviors: trusting teams to self-organize within their scope, encouraging collaboration across functions, and focusing on outputs/outcomes rather than hours worked. Leaders should practice delegating decision-making to teams and fostering a culture of continuous improvement. In short, they transition from being task masters to being enablers – providing clarity and removing obstacles, while allowing teams more autonomy. This can be challenging, as it requires overcoming reactive impulses (e.g., the need to control every detail), but it is crucial for faster flow. By “supporting testing of new approaches and learning from quick adjustments, instead of sticking strictly to preset plans,” leaders create an environment of trust and motivation in the Delivery context. From Delivery to Adaptive Topology: This shift demands an even deeper leadership transformation – from a results-oriented agile mindset to a truly innovative and learning-focused mindset. In moving to an Adaptive topology, leaders must fully embrace Creative leadership. They need to cultivate qualities like visionary thinking, humility, curiosity, and systemic awareness . Practically, this involves encouraging experimentation and accepting the risks of failure as opportunities to learn. Leaders must focus on outcomes and customer impact over output, which means guiding teams with a compelling vision and then giving them freedom to discover solutions. Developing a culture of empowerment and trust is paramount : agile/adaptive leaders “cultivate a culture of trust and empowerment, encouraging team members to take initiative and innovate,” which fosters an environment where experimentation thrives. Many traditional management habits (e.g., top-down decision making, extensive upfront analysis) must be shed in favor of facilitative leadership, coaching, and adaptation. According to Anderson and Adams (creators of the Leadership Circle), the “innovative, agile, adaptive” organizational cultures of the future require Creative leadership – reactive, compliance-driven leadership cannot generate the level of engagement and innovation these organizations need. Thus, leadership development efforts should focus on building creative competencies (such as relationship building, strategic foresight, and self-awareness) and transforming leaders’ mindsets from controlling to inspiring . This often involves personal development work, coaching, and hands-on experience in agile ways of working. As leaders grow into this new mindset, they enable their organizations to fully realize the benefits of an Adaptive topology. Conclusion Aligning leadership style with organizational topology isn’t optional — it’s decisive for performance. Shifting from Resource → Delivery → Adaptive is never just about moving boxes on a chart. It also demands a parallel shift in leadership: Reactive → Creative . The two evolutions are inseparable. Organizations that chase adaptability without Creative leadership will stall. Leaders who try to operate creatively inside a rigid Resource structure will suffocate. Both maps — the Leadership Circle and Org Topologies — point to the same truth: you can’t elevate the system without elevating how you lead. The takeaway is clear: as companies push toward greater agility and innovation, they must invest in Creative, growth-oriented leadership at every level. Leaders who learn to act from purpose and vision, not fear and control , create the conditions for truly Adaptive organizations — ones capable of sustaining high performance in a world of constant change. Sources The Leadership Circle – Overview of Creative Competencies vs. Reactive Tendencies The Leadership Circle – Reactive and Creative Leadership Definitions Anderson & Adams – “Reactive to Creative Leadership” (Mastering Leadership excerpt) (emphasizing need for creative leadership in adaptive cultures) Kestria Insights – “Adaptable leaders: Embracing agility and lifelong learning” (on empowering leadership in agile transformations)

- Aligned Autonomy at Scale (from Spotify Model)

“Aligned Autonomy” is a concept that aims to strike a balance between autonomous decision-making and alignment with organizational goals and values. The concept suggests that employees should have the freedom to make decisions and take actions autonomously, while also being aligned with the overarching objectives and principles of the organization. "Aligned Autonomy" as a concept has been referred to in various sources, to name a few: “Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us” by Daniel Pink “Turn the Ship Around!” by L. David Marquet “Empowerment and Organizational Development” by Bernard Bass and Bruce Avolio Another source is Henrik Kniberg , a famous Swedish agile coach and org consultant. Henrik coached at Spotify around 2012 , where he described their unique scaling model, initially proposed by Joakim Sundén and his colleagues. Henrik created a cartoon series that sparked worldwide interest and became known as the "Spotify Model." As a part of explaining how Spotify's ways of working were unique, Kniberg drew an image that describes the special relationships between the teams and management at Spotify: Aligned Autonomy. Image by Henrik Kniberg This image describes the relationship between team alignment and autonomy as a two-dimensional matrix. Team autonomy is on the horizontal axis, and team alignment is on the vertical axis. According to the matrix, autonomy marks the extent to which a team can make decisions about its work. Alignment symbolizes having a common purpose. Upon examining the image, it is evident that, according to the creator, management plays a crucial role in connecting the two. Key insights to derive from this matrix: Alignment and autonomy are not different extremes of the same continuum More alignment doesn't mean less autonomy We need both (alignment and autonomy) to achieve a high-performing organizational setup. In this article, we ask ourselves: Which organizational design allows multiple teams to collaborate at scale with high autonomy and full alignment? Alignment (for Purpose) Alignment is having a shared purpose. When teams are aligned, they pursue the same goal (as exemplified by Kniberg's "crossing the river"). Alignment is about getting the noses in the same direction and working toward a shared purpose . Management sets the boundaries and decides on how much autonomy is given to the "workers". Also, they are responsible for laying the groundwork for alignment. In other words, managers must effectively convey the "why", with strategy and purpose. Alignment and autonomy are closely intertwined, with management playing a crucial role in connecting the two. Alignment can be structured by management in many ways (by assigning coordinators or organizing for self-regulation), and it needs to match the granted level of autonomy (people cannot self-organize when a manager is (micro)-managing them). Autonomy (for Agency) For Spotify and other great companies, autonomy is a degree of freedom that teams have to act within the aligned purpose. Management "gives" autonomy to teams. These days, a common term for this phenomenon is agency-degree of freedom. Intelligent agents are given the freedom to act independently for the benefit of a shared purpose. While developing organizational topologies, we have discovered new insights about Autonomy and Alignment that differ from the Aligned Autonomy model presented by Kniberg. Dimensions of Autonomy Trying to establish autonomy in a group, for example, by creating autonomous teams, has become commonplace in most organizations. The management discussion on controlling work and outputs has shifted toward granting mandates and determining the degree of self-organization. The question is no longer whether teams should be more autonomous or not. The question is where that boundary lies. Richard Hackman, Professor of Social and Organizational Psychology, provides a powerful illustration of the options: Levels of self-management by Richard Hackman https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Team By "autonomy of teams," most organizations mean the second column per Richard Hackman's model above: Teams must be granted the authority to "execute the task" and "monitor and manage work processes." This is the bare minimum of self-management. There is no self-organization when these two permissions are not granted to the teams. Some organizations have tried the next level of "self-designing teams," where the teams not only execute and monitor but also "design the team and its context." We have experienced these experiments in LeSS-inspired adoptions and can confirm that this significantly enhances teams' agency. Designing for Autonomy in a Multi-Team Environment Do you agree that an individual team's speed is an interesting indicator of organizational performance? Are we truly measuring organizational performance when we examine a single team? Consider that the Billing team can be extremely fast at implementing a new Billing rule, but delivering the overarching customer journey, which requires contributions from many other teams, may take months. For a fact: the fewer (blocking) dependencies a team has, the more autonomous it is, the faster it can deliver product backlog items end-to-end. On the Org Topologies map, making org units (such as individuals, teams, or AI agents) faster is a horizontal move. Units can be formed more quickly by acquiring skills, insourcing skills, removing dependencies, and reducing the need for certain skills through automation, among other methods. In a multi-team environment, such a change is not a single-team transition but a coherent transformation of the larger ecosystem. In the picture below, three teams have merged to create a more autonomous CAPS-2 team with reduced skill dependencies on other teams. Analysts, testers, and front-enders now work as a team in the same cadence. The new CAPS-2 team possesses a higher degree of autonomy. They can decide on solutions as a group and handle more complex work at the capabilities level without needing assistance from others. However, they remain dependent on the back-end team. Transition of an ecosystem Note that such a movement is an organizational design change, not simply a policy or process change. Designing for Alignment in a Multi-Team Environment Similarly, creating alignment in a multi-team environment is not a mere manager's blessing: "thou shalt now be all aligned." People need to be aligned to complete a shared challenge. The question is: how can we arrange this to happen? What kind of alignment can we think of? There's alignment through external coordination and alignment through collaboration. Imagine a big room planning event (similar to Product Increment Planning in SAFe, for instance). The teams are gathered for a few days. They are presented with a strategy. The product board is filled with cards of different sizes and values. Teams are facilitated to identify mutual dependencies. The dependency manager connects cards with strings, and a detailed three-month plan is crafted upfront. Managers, coordinators, and teams are now aligned and understand how to manage the plan's execution and track dependencies. The teams are now free to proceed to their desks and begin work. Are those teams aligned? Yes, they are aligned. There is a shared purpose and a common plan to achieve this goal. Cross-team meetings will be organized by the coordinators to compare the plan with the actual state and make necessary course corrections. As a result, the teams' work queues may change, reflecting the actual progress toward delivering value as a group. Is it good enough? Not really. Remember that we need alignment to deliver a shared challenge. The concept of a detailed plan, upfront identified dependencies, and external coordinators to manage individual teams will reduce the possibilities for cross-team collaboration. It increases the team's ability to work independently, but does not equip the teams to see the broader picture of the shared challenge. Setting up for alignment through collaboration. We believe that external coordination as a means to align is weaker than giving teams the mandate to align with each other through collaboration. The success of this approach will depend highly on the team composition. Designing cross-team collaboration requires thinking about autonomy and alignment. We want to be in the top-right corner of the Kniberg matrix, where teams are highly aligned and have high autonomy. Org Topologies offers a model for designing collaboration at scale. It identifies four distinctive levels of a team's focus: Four levels of focus These four levels are essential for designing effective collaboration. As the teams' scope of work expands from task focus and capabilities focus up to partial business and whole business focus, the teams' scopes of work start to overlap. This is traditionally seen as a problem we want to avoid. But we can also see this as an opportunity for teams to collaborate. Overlapping responsibilities are traditionally viewed as a problem to be avoided. However, teams now have a shared scope of work and can join forces to attack big common challenges: Shared scope of work Alignment through collaboration is a result that emerges from overlapping responsibilities and shared goals. Aligned Autonomy at Scale We have discussed the different forms and shapes of autonomy and alignment. To create an organization where teams have full autonomy (not isolation) and can remain perfectly aligned (through collaboration), we need an organizational design that provides wide mandates on both the scope of work and the skills required to perform that work. Design for collaboration It is the space where highly collaborative practices, such as Multi-Team Product Backlog Refinement and Joint Sprint Reviews , become the norm. Refer to Elevating Katas™ to learn more about designing collaboration at scale. Such an organizational design requires organizations to experiment with abandoning the idea of Independent, autonomous teams and instead creating cohesive, interdependent multi-team units: a team of teams. At Spotify they created a space for collaboration with many cross-team structures and meetings: High collaboration at Spotify Over time, through practice and tight collaboration, a team of teams will develop a broader understanding of the product. They will start to think holistically from the business and customer perspectives and realize that they need each other to make significant changes in the product. Autonomy at scale requires a broad scope of work and skills to facilitate alignment through collaboration. This might sound utopian, but don't worry. This is a "perfection vision" for your transformation. You can aspire to it and gradually move your organization in this direction. You can also grow gradually by trying out practices from the Elevating Katas™ . At a super large scale (hundreds of teams), there can be multiple "teams of teams", each specializing in a business domain and a set of cohesive customer journeys. In the case of financial services, for instance, there can be a team of teams for Retail Banking and another team of teams for Business Banking. Management provides direction by setting strategy and priorities, along with product goals. The teams turn those goals into tangible products. Aligned autonomy at scale can be achieved through broad product knowledge (encompassing the scope of work, represented on the vertical axis) and a comprehensive skill set (encompassing the scope of skills, represented on the horizontal axis). Endnote: We do not claim that every individual needs to know everything and possess every skill. We claim that large groups of people can be mandated to multi-learn in both directions to acquire the capability of knowing everything and having every skill collectively as a group . © Roland Flemm and Alexey Krivitsky

- AI-Augmented Multi-Team PBRs

LeSS—an org design system for large-scale product development—describes Multi-Team Product Backlog Refinement as one of the key enablers of organization-wide adaptability. Multi-team PBRs are where teams learn from customers, stakeholders, and each other. This is where all the involved teams dive into the problem space to come up with innovative and effective product experiments. Forward-Looking Orgs with AI-Augmentation Today, AI augmentation offers a powerful and complementary capability: accelerating deep, multi-directional learning during PBRs without compromising the core LeSS design principle of simplicity. We can think of many AI applications that can streamline the learning process, especially in product backlog refinement events. Using my recent post on Never Read Alone , I explained how AI can enable teams to interrogate vast datasets , including user feedback, legal regulations, and competitor analysis, with just-in-time learning via AI-powered dialogs over any given corpus of knowledge. This amazing innovation must also be used during refinement. And not before or after—a critical aspect. A typical dysfunction of a PBR event is overpreparation by product managers and other expert roles who act as knowledge providers, turning the teams into students. Though it is essential for teams to learn, minimizing the associated process waste of knowledge transfer would be beneficial. Namely, applying AI right in the PBRs to learn and structure knowledge, by the teams directly, can dramatically reduce the need for an expert or a special role to prepare for these meetings. We predict that this will become increasingly common now, in the age of AI. AIs (even before the hypothetical emergence of AGI) are already more knowledgeable than any average subject-matter expert and can easily cross-pollinate between domains . Teams that find ways to learn from AIs will no longer need to rely on and wait for part-time human experts. Thus, streamlining the learning process makes it way lean er than imaginable. The main criticism of LeSS-inspired org design is the high cognitive load in teams, potentially caused by the constant need to learn and switch context. AI, when applied systemically and methodically, can reduce the burden of absorbing complexity by providing information in a clear structure, in smaller chunks, just in time, with runnable examples, etc. These a few examples I'm bringing above are very different from how most people currently see and use AI. Somehow, the whole narrative revolves around using AI agents as free labor. Although this is probably where many innovations will be made due to obvious economic reasons, AI is not limited to doing things. AI is not (just) a doer, it is a great teacher.

- Case Study: Studying LeSS Adoption at Poster POS Inc. with Org Topologies

Poster POS Inc. (or Poster) is a cloud-based SaaS automation for small-to-midsize businesses in the hospitality industry, also known as HoReCa (Hotels-Restaurant-Catering). The business was founded in Ukraine around 2013 and has shown a very high level of resilience since then. The HoReCa industry has been severely affected by Covid-19 and by the Russian war on Ukraine in 2022. Still, the company restored its profitability and even grew its B2B clientele in Ukraine during the wartimes. In 2021, the company has undergone serious reorganization, striving to increase its adaptability. Poster was inspired by the ideas from Large-Scale Scrum (LeSS) , such as global optimization with a whole-product focus and delivery of high-value work with customer-facing feature teams. This case study analyzes that transformation journey using Org Topology Scans (org scans). It covers three distinguishable organizational designs: Org scan of the status quo in Poster before the LeSS adoption, "Team-level Scrum" Org scan of the envisioned initial LeSS-Inspired blueprint (which drawbacks we timely rethought and eliminated) Org scan of the improved LeSS-Like org design implemented in 2021 as the scope of this LeSS adoption. The following chapters describe these three OT™ scans in detail. Heads-up! Video is Available There is also a talk by Alexey Krivitsky from the LeSS Conference 2023 featuring some of the ideas from this article: 1. Org Scan of the Pre-LeSS Structure "Team-Level Scrum" Before the LeSS Adoption started in the summer of 2021, Poster had around 50 engineers in the R&D department that were structured as: a dozen of development teams varying from 2 to 6 people; teams were built around a specific technology, a component, or a feature set; one separate infrastructure/operations team of several people; one small designer group , whose members mainly worked on individual task lists to support the development teams with visuals and UI sketches. According to the Archetypes of Org Topologies ™ , the development teams can be classified as Y1 (component development) and A2 (development of a narrow feature set). What is typical for these archetypes is that every team had an individual team-level backlog (task/feature list) that was managed by a team-level "PO". Most of the teams, especially the bigger ones, also had a team lead - an interface person for the team and the ultimate solution-oriented decision-maker. The designer group can be seen as a Y0 (individual work). Two more departments, tightly coupled with the R&D were the "client onboarding" (3 people) and "1st & 2nd-line support" (25 people). This case study doesn't go into the details of those departments, keeping a focus on R&D and its radical transformation. The illustration below shows an org scan of Poster product department as of the summer of 2021 with Y0, Y1, and A2 archetypes. Analyzing the "Team-Level Scrum" Org Design According to the Org Topology™ mapping, all the archetypes of Team-Level Scrum are at the lowest levels -- they provide close to no organizational adaptability as they are narrowly specialized in tasks and individual features. That was why Poster wanted to improve its org design and planned the restructuring. The "Team-Level Scrum" org design is typical for many product development organizations of any size. It grows naturally as a company hires more people and forms new teams. It is also known as the "copy-paste Scrum adoption" antipattern, where Scrum is implemented as a cookie-cutter for each newly formed team. Scrum in such an organization is seen as a team-level way of working, where each team gets its own backlog and a backlog owner and starts working with iterations that are typically non-synchronized among the teams. Such an approach allows the teams to run a Scrum-like process individually. And from the team perspective, this is an efficient way of working, as it allows teams to keep focus and ownership on given product components or some narrow feature sets. This org design is also relatively easy to implement, which is why it is so widely adopted in the industry. But as the number of teams grows, additional complexity caused by inter-team dependencies increasingly slows everyone down. Hiring professional managers and applying project management tricks just make things worse. These practices add communication layers with hand-offs, bureaucracy, and processes to an already poorly designed engine. In such a model, even though each team has a sharp focus and might even have an illusion of progress by ticking off items from its individual backlog, the performance at the organizational level tells a whole different story. At the level of the R&D department (not just individual teams) in such organizations, we see slow delivery and low adaptability. This is a systemic view: paying attention to the interaction between the parts is as important as studying the parts. The lack of maneuverability (teams cannot easily switch to working on new things, as they don't have the necessary knowledge and skills), causes this type of organization to hire more specialists to perform specific tasks. This makes the system even more complex and degrades over time. Our experience is that at the size of around 50 engineers, these challenges start to emerge and become painful enough to make managers want to act on them. By the spring of 2021, the leadership team at Poster had recognized these drawbacks and was actively searching for an improved org design that would eliminate the forementioned problems. 2. Org Topologies™ Scan of Initial LeSS-Inspired Org Blueprint LeSS promotes org design based around long-lived cross-component cross-functional customer-facing feature teams . Such teams deliver and learn much better than narrowly specialized ones. By learning to work on things that they previously didn't know, feature teams continuously improve their adaptability. Therefore, the whole large-scale product development system based on feature teams could potentially over time get better at delivery and better at learning. These qualities enable faster value delivery and higher organizational adaptability: Faster value delivery comes from having teams that are learning to build products end-to-end. Higher organizational adaptability comes from teams that are learning to work on the whole product. If the company's optimizing goal is faster value delivery and higher organizational adaptability, the LeSS-inspired org design is the most consistent with those goals. In such an organization, the product owner will only have to re-order the product backlog items to change the course of development for all the teams. No reorganization is required to re-align the product development organization to adopt a changed product strategy. The product development organization is agile and can adapt to changing requirements just in time. Already during the next refinement session (in LeSS terms "multi-team product backlog refinement" or PBR ) the teams will start learning that new high-value work. At Poster, the leadership team plus all the developers and business stakeholders were trained in LeSS and its ideas before adopting this org design. It took around two months to arrive at informed consent on which org design to use. During that time, several org design blueprints were created, compared, and contrasted. The following illustration depicts a scan of the anticipated org design blueprint (later it was discarded due to the reasons listed below). This org design consists of three "value areas": B2B (the core product). B2C (the new, innovative product development). Growth (product tuning to increase customer activation and retention). The B2B area was the largest and was planned to have the biggest investment. Four feature teams were planned to share a single product backlog. Very much a LeSS-like structure. This design can be classified as B3. The other two areas had fewer investments and were to have a single team each. They are A3-level as each team would have an individual feature-centric product backlog, i.e. having a relatively narrow product focus. No changes for the infra/ops team and the designer group were planned. Analyzing the Initial LeSS-Inspired Org Design As it can be clearly seen from the org scan above, several single-team value areas were envisioned (B2C and Growth), even though the leadership team at Poster had already embraced the idea of LeSS and broader product definition . What was driving the management to choose a sub-optimal org design? And what were the shortcomings of such an org design? Why not allow all the teams to work together on the entire product as LeSS proposes? From our experience as org consultants, the most voiced arguments for creating narrow-focused single-team value areas are: Investments & Innovation : "As we have never been able to work on X and Y, let's create an X-team and a Y-team". Experts & Ownership : "There is an expert in Z, let's make her a product owner and give her a Z-team". Focus & Accountability : "Teams need to have a clear focus and accountability for each component; otherwise the code becomes a mess". Learning & Specialization : "Knowing everything is impossible, we value and need the specialists". We often hear these kinds of objections when a LeSS-like org design is proposed. At Poster, it was a mix of the first two arguments that produced the initial blueprint. Such arguments are hard to counter, as they stem from deep beliefs in the convictions of the leaders. They have not yet seen a different set-up than their own, and all their experiences and career successes confirm that what they already know is working. This confirmation bias automatically disproves all new ideas. An organizational design is the sum of the mental models (beliefs and value systems) of the people who created it. But all mental models are personal. If we want the managers to own (create and support) a new improved org design, there is not much choice but to work with them to help them see new options, help them challenge, and eventually have them adapt their mental models. The breakthrough of discarding this model and going with a simpler org design (LeSS for all the feature teams) came from a realization that B2C and Growth can still be worked on, if needed, even with all teams sharing the same product backlog simply by setting the order of the items. Also, the people from the teams voiced a strong argument supporting wider collaboration of the teams: "Let's learn to work all together as one, isn't that why we want to go with LeSS in the first place!?". To make such powerful conversations possible, during the preparation/learning phase, all the team members and the management representatives were regularly gathered for open-space-like events. That shared context helped them to uncover and collaboratively agree on many open questions. Eventually, building informed consent to start with a simpler holistic org design, is described below. The real goal of the org design activity is to create the simplest org design possible that would still work. More processes and roles can be added later when needed. But starting with a simpler org design empowers the people to own it and improve it. 3. Org Scan of LeSS-like Org Design at Poster It took us several months to arrive at a simpler org design with no single-team areas. An org design that everyone was happy to start with. An org design that would barely work, but was understood by everyone to own it from day one. The improved org design would have all the feature teams sharing work and working across the product. That would classify them as C3-team. Analyzing Org Design: "LeSS for the Whole Product with All Teams" This simpler org design covers many raised concerns above: Investments & Innovation: In this org design, when there is a need to work on Y or Z, these items simply get prioritized and put higher on the common product backlog. And then the teams (one, several, or all) will start working on them. There is no need to create specialized teams. If, for instance, the B2C or Growth topics become the most important, nothing stops the Product Owner to put those items on the common Product Backlog and let the teams start to refine and deliver them. This way, in every Sprint, the PO can decide with the teams how many teams should be working on these topics. This creates a fluid org structure where pairing between teams and topics happens just in time. In contrast to statically defined separate org units (value areas) per topic. This way, an organization stays highly adaptive, as it can decide to jump on any opportunity without any re-organization efforts. Experts & Ownership: Shared work on the common product backlog by all the teams leaves a lot of room for collaboration with experts. But this collaboration happens only on high-value work (just-in-time). Such a modus operandi eliminates the creation of proxy or clerk-type product owners. And welcomes the teams to work with many different experts and keep learning from them. Focus & Accountability: Good focus and a strong feeling of ownership in teams are still possible, even if they work broadly on the whole product together. This can be achieved by applying practices of Continuous Integration , Mob Programming , multi-team work sessions, and other means of inter-team decentralized coordination . Learning & Specialization: Specialization is great. And learning to work broadly on a product by delivering customer value is great, too! These goals are not mutually exclusive. There is no false dichotomy, as we need them both. The LeSS-inspired org design allows the teams to pull items that they are capable of doing (utilizing their existing skills) as well as working with other teams on new things (acquiring new skills). As is seen in the next illustration of a flow scan of Poster after the change, tight multi-function collaboration and the presence of feature teams contributed positively to shortening lead times for features. A big change for the developers was expanding the Definition of Done to include non-development activities like customer onboarding. Now, a feature is seen as done only after the first customer(s) use it. That created a powerful feedback loop to the teams and affected the way they design, work on, and deploy the features. Weekly collaborative requirement refinement sessions became a collaboration opportunity for all the stakeholders and the experts: customers, product managers, designers, representatives of the support department, client onboarding, and engineering managers gathered with the feature teams. That accelerated the processes of forming requirements. And importantly, it has ensured a much better shared understanding of what is expected to be done. This process contributed to minimizing lead times for features not only by reducing waiting for specifications but also due to minimized rework because of improved alignment. Note, how the collaboration style of many groups has switched to facilitating, supporting the work of the heart of the new org design -- the feature teams. Conclusions The described LeSS adoption at Poster and its detailed org scans can be illustrated as an org topologies mapping provided below. Y0, Y1, and A2 archetypes were mainly converted to a C3-level organization practicing holistic product development and optimizing for adaptivity in learning and delivery. Observed Adaptability and Resilience Since the end of summer 2021, Poster and its feature teams have been operating in this new mode. They went through and recovered from the Covid-19 lockdowns. Now, as of writing, this case study in winter 2023, they have spent almost 300 days serving its impressive B2B customer base during the wartime in Ukraine. They even managed to grow their clientele, a real sign of high resilience! Business resilience comes from high organizational adaptability. And high adaptability comes from an org design that enables and nurtures it. Therefore, org design is an essential skill to be mastered by management. © Written by Alexey Krivitsky and published with permission from Poster POS Inc. This experience report presents a personal view on the change story by the credited writer. Should you have alternative views or additional details about this particular company's change story, please do not hesitate to contact Org Topologies and submit your version for publishing.

- Improving leadership’s performance in their organizational design